Individuality often has no place in the enterprise software space. In a market where a single contract can easily run into the millions, homogeneity is the herald of reliability and serves to reassure buyers of the worth of their potential purchase.

So it’s natural to think a company in the expense report management business would keep it simple and play it by the book. But one look at Expensify is enough to tell you that this is a company that never even looked for the book.

Expensify’s origin story is one of a scrappy group of developers who turned travel into a catalyst for ideas and stuck together through highs and lows, ending up building one of the most unexpectedly original companies in enterprise software today.

Right from its famous “workcations,” to its management structure and its decision-making policies, Expensify has it in its DNA to eschew so-called best practices for its own ideas — a philosophy rooted in its founder and early team’s P2P hacker background and do-it-yourself attitude. As a result, Expensify is atypical of startups in many ways, inside and out.

Founder and CEO David Barrett made it clear his company was different in our first call itself: “We hire in a super different way. We have a very unusual internal management structure. Our business model itself is very unusual. We don’t have any salespeople, for example. We’re an incredibly small company. We focus on the employees over the bosses. Our technology stack is completely different. Our approach toward product design is very different.”

That description would make some people call Expensify weird even by startup standards, but this essential difference has set it apart in a space dominated by giants such as SAP Concur and Coupa. And that’s ultimately been to its benefit: Expensify reached $100 million in annual recurring revenue in 2020, with hefty 25% EBITDA margins to boot. There were also rumors of the company planning to go public during our interviews for this EC-1, but they stopped speaking to us in March, and now we know why: Expensify confidentially filed to go public on May 3.

Expensify’s origin story is one of a scrappy group of developers who turned travel into a catalyst for ideas and stuck together through highs and lows, ending up building one of the most unexpectedly original companies in enterprise software today.

When David met Travis …

To truly understand Expensify, you first need to take a close look at a unique, short-lived, P2P file-sharing company called Red Swoosh, which was Travis Kalanick’s startup before he founded Uber. Framed by Kalanick as his “revenge business” after his previous P2P startup Scour was sued into oblivion for copyright infringement, Red Swoosh would be the precursor for Expensify’s future culture and ethos. In fact, many of Expensify’s initial team actually met at Red Swoosh, which was eventually acquired by Akamai Technologies in 2007 for $18.7 million.

Barrett, a self-proclaimed alpha geek and lifelong software engineer, was actually Red Swoosh’s last engineering manager, hired after the failure of his first project, iGlance.com, a P2P push-to-talk program that couldn’t compete against Skype. “While I was licking my wounds from that experience, I was approached by Travis Kalanick who was running a startup called Red Swoosh,” he recalled in an interview.

Founded by Kalanick and Michael Todd in 2001, Red Swoosh had had many ups and downs by this point. Very much on the legal side of things this time, Kalanick wanted to build a proprietary peer-to-peer content distribution network (CDN) for clients that needed to move very large files, such as media companies, at a lower cost compared to traditional CDNs. But by 2005, the startup had suffered the loss of its co-founder and technical team.

Later that year, however, Kalanick managed to raise funding and win a deal with AOL (which remains, in evolved form, TechCrunch’s current parent company Verizon Media), and soon began prospecting for engineers on P2P forums. Barrett says that Kalanick actually recruited him via the p2p-hackers mailing list and was very transparent. “[Travis was] completely honest about the state of business,” Barrett was quoted saying in Brad Stone’s book “The Upstarts,” his history of Uber and Airbnb. “He was persuasive, compelling and candid.”

Red Swoosh’s landing page circa 2006. Image Credits: Tom Jacobs

Despite the air of controversy around P2P and a wink to pirate speak on its blog, Red Swoosh was fully legitimate and had significant potential for businesses. With an ad-supported free tier, it could be relevant for anyone, but its paid offering was particularly useful for companies with large needs. For instance, the startup bragged at one point in a fake letter to Steve Jobs that it could hypothetically save Apple $15 million over Akamai’s bandwidth costs, catching some attention.

Despite being addressed to Apple, we suspect that the letter’s intended readership was instead Akamai. “[Kalanick] always assumed Akamai would buy his business,” Akamai’s former CEO Paul Sagan later told Adam Lashinsky for his book on Uber, “Wild Ride”.

But Red Swoosh had to roll up its sleeves to actually make this an option. Luckily, rebuilding such a product was precisely what the team assembled by Barrett had the skills and passion to do. Indeed, all of them were engineers with a love for P2P. “We had a lot of old technology, so we cleaned up that technology, expanded it, rewrote a lot of it, added some new customers, then we were acquired by Akamai,” Barrett explained later.

With all that context, it’s easier to understand why an expense company like Expensify does things like building its own distributed database, why it so often preferred building over buying, and why its culture is still reminiscent of the P2P hacker ethos.

The adventurer mindset

The Red Swooshers weren’t pirates for a living, but they were very much adventurers in their own way. By the time he joined Kalanick’s startup, Barrett had already been to 22 countries on a round-the-world trip in 2002-2003, all while working on tech and P2P projects. This proved to be a life-changing experience owing as much to the traveling as to the plentiful misguided friendly warnings and “expert advice” that Barrett received before he left. His takeaway? “Basically everyone is wrong about basically everything.”

That conclusion became a guiding principle for his work, and eventually, Expensify. He learned that it’s much easier to figure it out yourself than trying to find advice that will work for you or your company. VC Blake Bartlett, who sits on Expensify’s board, says he often points out this trait to other founders: “The ability to not just follow best practices because they are best practices, which I think a lot of startup founders do — ‘This is the way everybody else has done it, so that must be the best way,’ versus viewing it from a first-principles standpoint.”

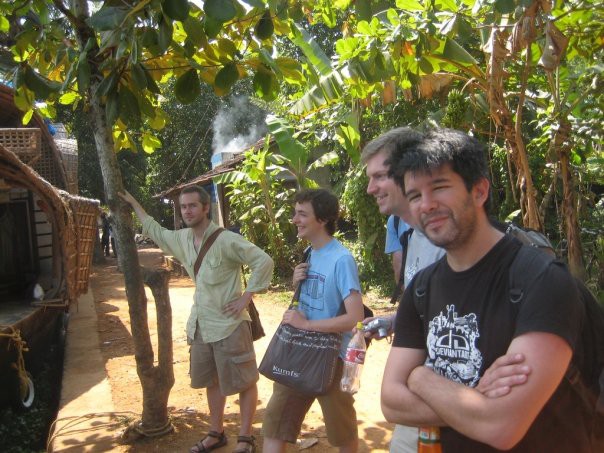

Barrett’s taste for traveling far and light was also something he had in common with Kalanick. “David and Travis are quite different people, but they are both adventurers,” former Red Swoosher and early Expensify employee Tom Jacobs told TechCrunch. One could say the same of the Red Swooshers who later joined Expensify — they didn’t blink an eye at the idea of being productive and saving money while going on “workcations” abroad, from Thailand to Mexico to India.

A Red Swoosh “workcation.” (L-R): David Barrett, Tom Jacobs, Curtis Chambers and Travis Kalanick. Image Credits: Tom Jacobs

Looking back, this period foreshadowed what would follow. The Red Swooshers became a tight-knit group that was only natural for Barrett to tap when founding Expensify. Their work also paved the way for Red Swoosh’s acquisition by Akamai, which was a new bonding experience for the team, although in a drastically different manner.

All good things …

Akamai’s deal to acquire Red Swoosh in April 2007 included hiring its team. At the time, an Akamai spokesperson said that the deal was “a technology acquisition” and that the company gained skilled software developers and unique client-side technology that would augment its own content distribution business.

But there were doubts that this was actually the case. For starters, the deal was quickly interpreted as Akamai neutralizing a potential threat. “Many had said that P2P caching could dislodge Akamai from its current dominant position. Fat chance — Akamai, it is clear, is more fierce in protecting its turf than, say, Microsoft. It just uses its hefty stock market capitalization to buy out possible competitors,” Gigaom wrote when the deal was announced.

It’s unclear whether Red Swoosh was ever meant to survive as a standalone offering — maybe that wasn’t the point at all. Talking to Lashinsky for his book, Sagan provided additional context into why Akamai made this acquisition: “Swoosh was a way to hire a bunch of pirates to get it done.” (“It” being his desire to add P2P to Akamai’s offering.) “I used the rebellious nature of Travis and Swoosh to get something done that I had been banging my head against the wall to do for years,” Sagan said.

It might have worked out for Akamai in the long run. After all, the “peer-assisted” NetSession Interface it launched in 2011 was based on P2P technology originally developed by Red Swoosh with continued contributions from Tyler Karaszewski, now a senior software engineer at Expensify.

Yet, seeing Red Swoosh reincarnated as an Akamai offering years later was far from what Kalanick and the others envisioned. As Jacobs told TechCrunch, they had hoped to keep on working on Red Swoosh as a team and were unhappy when Akamai prevented that from happening. This might have been somewhat naive — after all, Akamai’s press release stated outright that “the Red Swoosh team will be integrated into Akamai’s existing engineering team in California” — but it was extremely frustrating for them nonetheless.

In a sense, what followed was expected: Kalanick left Akamai in August 2008. By that time, most Red Swooshers were already out, but Barrett’s own departure would be more revealing.

“It’s all about consensus”

Barrett’s quite open about being fired from Akamai. In 2010, his bio said he’s “perhaps best known for his high-profile termination from his previous employer, which not only earned him his own dedicated TechCrunch story, but was the subject of an MIT ethics debate regarding the boundaries between personal and professional communications.”

Long story short, an article quoted Barrett criticizing the plan for a “music tax” to be universally added to internet bills. What he didn’t know, he later explained, was that Warner Music was supporting this project and was also an Akamai customer. To make matters worse, the piece didn’t mention that he was speaking as an individual and not on behalf of his employer. In the end, he managed to reach his one-year vesting cliff, but was eventually let go in April 2008.

Barrett didn’t intend to lose the job, but the episode reflects his disposition for bold stances. As you may remember, Expensify made headlines in October 2020 when it emailed all of its subscribers, urging them to “protect democracy” by voting for Joe Biden in the U.S. presidential election. “Anything less than a vote for Biden is a vote against democracy,” Barrett wrote in a long email.

It’s perhaps not as well known that Expensify’s team had been widely consulted about it. Not just because this was clearly going to rock the boat, but because this is how Expensify operates in general.

Former employee Jason Kruse recalls that decision-making at Expensify was never a top-down decision. “It’s all about consensus,” Kruse said, adding that he’s trying to implement the same ethos at the startup he’s co-founded since then, Privacy.com. He connects the philosophy directly to Barrett’s P2P background: “Distributed systems are all about consensus. An example is the bitcoin blockchain: You basically need thousands of different nodes, most of which you don’t control, to all agree that something happened — the transaction, in this case. That’s what consensus means in distributed systems, and Expensify has a lot of analogies to the way they run the company.”

Red Swoosh and Akamai both gave Barrett a chance to delve deeper into his passion for P2P. And after Akamai, he had plenty of free time to work on the idea that would eventually become Expensify, and which he had already started pursuing “on nights and weekends.” Since he had some savings — and he well remembered how everyone had tried to discourage him from his world trip — he decided to go solo and keep it quiet. “Basically my girlfriend knew, and that was it,” he said.

A fresh start

Fast-forward a few months and the fledgling idea was starting to sound more like what Expensify would eventually become. Barrett’s initial idea was to create a prepaid card he could give to homeless people whom he walked by every day in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, but he pivoted his pitch to a product that seemed easier to get approved by banks and financial institutions: A combination of a corporate card and expense reporting.

Expensify at TechCrunch50 2008. Image Credits: magerleagues (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Hoping to get more validation and convince potential financial partners, Barrett applied for TechCrunch50 2008, which got him a table in the DemoPit, a Startup Alley predecessor. “That was what triggered me to reach out to my co-founder,” Barrett said, speaking of Witold Stankiewicz, who was also Barrett’s first hire for Red Swoosh. Soon, other former Red Swooshers — Jacobs and Curtis Chambers — would also join.

Kalanick also jumped in as an early advisor, investor and supporter. His blog post from September 2008 is a good testimony of the startup’s initial pitch: “Empower small-business employees, independent contractors and sole proprietors with easy tools for PAINLESS expense reporting … Expensify accomplishes this with three main Expensify components,” he wrote, listing the expense card, the receipt capture and upload feature, and the dashboard.

Eventually, the idea grew into something more tangible. From TC50 onward, Barrett and his co-founder couldn’t help but see that the expense reporting part resonated with lots of people. In addition, better smartphone cameras soon made the receipt capture feature more than wishful thinking, and even the expense card made a comeback in Expensify’s offering in 2019. As for helping the homeless, Expensify went full circle in 2020 with its COVID-19 relief campaign and the launch of its charity, Expensify.org.

All this only makes it striking how Expensify has retained its individuality despite its maturity 13 years on, and as we’ll find out in Part 2 of this EC-1, that’s because it puts an unusual amount of thought and effort into developing a unique work culture.

Expensify EC-1 Table of Contents

This EC-1 was serialized starting early May and continuing through early June.

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Culture

- Part 3: Expansion and remote work

- Part 4: Engineering and technology

- Part 5: Business model

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.