Michael Bloomberg is an unrepentant capitalist who, as he says in his 2017 book A Climate of Hope, is “not exactly your stereotypical environmentalist.” Yet over the past decade, Bloomberg has become arguably the biggest environmental philanthropist in the world — especially given the $500 million investment Bloomberg announced last month that he would soon make in rapidly moving the U.S. “Beyond Carbon,” off both coal and natural gas and to a “100% clean energy economy.” How did this happen?

It turns out one of the biggest factors in Bloomberg’s green transformation has been his friendship with Carl Pope, the longtime former head of the Sierra Club, whom Bloomberg first met about a decade ago, as Mayor of New York.

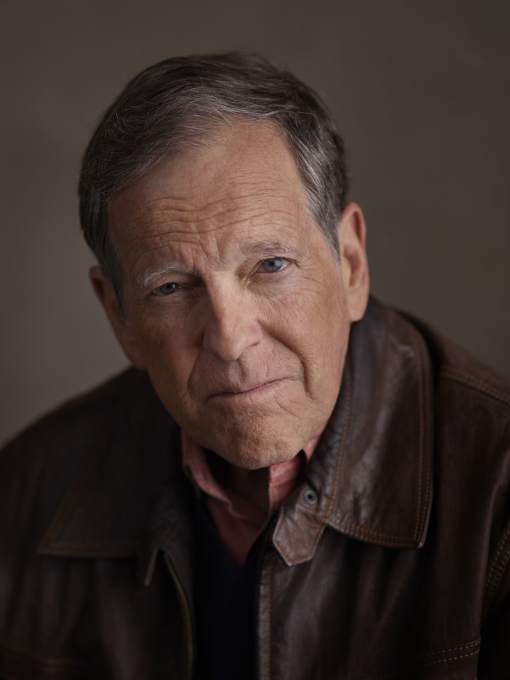

Pope is not exactly a household name, but nonetheless at this point can probably be called one of the most influential environmental activists in history. He wears a leather jacket and a weathered-looking sweater on the cover of Climate of Hope alongside Bloomberg’s suit, tie, and flag pin.

The two co-authored the book — and not just in the sense that Pope ghost-wrote Bloomberg’s opinions, as happens regularly when busy political and cultural celebrities take on a lesser-known co-author for some glamour project they may barely even read. A Climate of Hope is an extended dialogue between Bloomberg and Pope, with the two alternating chapters throughout and at times even disagreeing on potentially important issues.

What there’s no disagreement on, however, is that Pope “convinced” his co-author to dive into massive environmental spending (a feat accomplished in part by showing the health-conscious Bloomberg the numbers on how lethal coal can be).

Pope is no stranger to controversy — perhaps unsurprising for a nonprofit leader who has raised money well into the nine figures. He’s a “pragmatist,” as he says many times in the interview below, which depending on who you ask either means compromise to the point of being compromised, or simply that he has a knack for actually getting things done where others merely talk.

His legacy has previously been associated with taking money from natural gas executives in a fundraising bid some saw as necessary and others called ethically tainted; with overlooking people’s polluting individual choices to buy large cars and even bigger homes; and with “looking forward to an active partnership” with Republican leaders when it was obvious they weren’t completely on board with key tenets of the environmental movement.

But Pope has also been equally or better known for pushing the Clinton/Gore administration to be better on emissions; preventing neoliberal environmentalists from adopting a nativist stance on immigration; championing a more diverse and inclusive environmental movement; and now, of course, with potentially ending the use of carbon fuel in America.

Despite 30+ years in the public eye, Carl Pope is a relatively private person who doesn’t seem to like to talk much about himself. So for starters below, I wanted to see if I could figure out what makes him tick.

Because if we could get into the heads of people who persuade billionaires to act against their short-term economic interests, with the bigger human picture in mind, maybe we could do it more often.

Then our conversation moved on to NASA, Ro Khanna, Tesla, AOC and the Green New Deal, and more. And in a soon to come follow up piece, I’ll talk with Pope about the details of the Beyond Carbon plan, including how he was able to persuade Bloomberg to take it on, and some areas of controversy that could arise as the $500 million is distributed.

All of this, after all, is part of what it means to think about the ethics of technology — Pope and Bloomberg’s work, love it or not, is certainly an attempt to reform or transform some of the most influential technologies human hands have ever touched.

How do we motivate people of all backgrounds and means to help make changes for the greener? How do we know what the right changes are to make? How do we grapple with the ethical dilemmas involved and the compromises that can seem to be required?

(Oh and by the way: in the weeks since I spoke with Pope, I have mostly been skipping big evening meals and eating more healthily in the afternoon. So at least there’s that!)

Greg Epstein: I have enjoyed discovering you as — I would even say as a historical figure, though important parts of your story are yet to be told.

I’d like to hear a bit about the key developments in your life that gave you the ethical perspective that you have.

Carl Pope: I can tell you some things about my childhood and my formation. Which particular ingredients formed my ethical perspective, I’m not sure I’ll be able to tell you, but I’ll tell you some things [that might] help.

My ethical perspective comes from the liberal side of the American spectrum of the 50s and 60s. Though my two years in India were probably very important [also].

I was born in 1945, at the end of World War II. So, I was technically a member of the Silent Generation, but really, a very early Boomer.

I grew up outside Washington, DC: Montgomery County, Maryland. My father worked for the federal government, for the Rural Electrification Administration in the Department of Agriculture. My mother worked some of her life in educational lobbying organizations, the Land Grant College Association and the National Association of State Universities.

They were liberals, and not particularly partisan, because in that era many of the liberals in Maryland were actually Republicans.

The very first television program I remember watching was, my mother dragged me out at the age of 9 to watch the Army-McCarthy hearings where Joe Welch challenged McCarthy. Then I grew up, and probably formed my most formative political attitudes during the late Eisenhower and Kennedy years, and became very interested in public policy. In high school [I thought] I would probably go work for the Peace Corps or UN or the State Department in international development work.

I went to college at Harvard and studied Middle Eastern affairs there. Then the Peace Corps [where I] spent two years in a small village in Eastern India, working on family planning.

Back to Washington. Thought I was going to go to graduate school, but I got myself a job right out of Earth Day, working as an environmental lobbyist in Washington. I found that much more interesting than graduate school; a couple years later I moved to California, started working for the Sierra Club.

Growing up in Montgomery County, I read The Washington Post. In that era {WaPo] had a society section that really told how the city actually worked. You didn’t actually find out how the government worked by reading the front page. You found out how government worked by reading the style section.

So I grew up with an ideologically liberal but pragmatic perspective on how things worked, from my childhood. Then I got a solid grounding in how things might work differently, from my two years in a small village in India.

And the other thing that happened along the way was, when I was in college, I was active in both the Civil Rights Movement and SDS, the anti-war movement. All those things in the 60s [were] a very important part of shaping my political and ethical attitudes.

Epstein: Thank you. Regarding the influence of the Washington Post society page: was that in the era of Sally Quinn? I worked closely with her after she moved from Washington society to religion coverage.

Pope: Sally Quinn came in at the end.

Epstein: But that sort of writing, about the various controversies of Washington dinner parties and-

Pope: She wasn’t the only one. She was, for me, it was literally, you would read about a bill passing or not passing and then you would read why it passed or it not passed, and then you would read why in the society section because it was about relationships.

Epstein: Interesting.

Pope: That’s the Washington Joe Biden is still talking about.

Epstein: Right. Well, and in many ways, it’s the Washington you’ve worked in. In A Climate of Hope you write about how in the Peace Corps, you saw the security guard at an Indian medical clinic die of cholera, weakened by his refusal to eat the “wrong” food according to his custom, which you say symbolized “how profoundly irrational and inflexible human dietary preferences are.” And you’ve been very reluctant throughout your career to go after people for their personal lifestyle choices, like what people want to eat.

Image via Getty Images / Kilroy79

Pope: You started out by asking me if I could tell you where my ethical perspective came from, and I’m probably the person best qualified to answer that question, [but] I don’t think I can really answer.

I think people don’t really know where the whole host of their preferences and temperamental things come from. People don’t do what they do because of what they believe.

They believe what they believe because of what they do. Behavior, mostly, comes first. We learn to have beliefs by acting on things and then we sort of create beliefs that make sense in our lives.

Why do I actually, today, still want to eat a big evening meal? There are whole societies where people eat small evening meals.

It’s not because I have scientific data which shows eating a big evening meal is the right thing to do. I actually suspect it’s not the right thing to do, and if I was just being totally health-conscious, I’d eat a big afternoon meal. But, I grew up eating a big evening meal and therefore, I believe in eating big evening meals.

Epstein: Since we’re talking about what you believe, I would be remiss if I didn’t ask you about what for me was one of the most fascinating chapters in your long career. In 1997, in partnership with Bartholomew, the Green Patriarch of the Orthodox Faith, you spoke to a group of interfaith religious leaders, and gave a public apology, as the New York Times called it, for the rejection of religion by your generation of environmentalists. How does your instinct to do that play into your current work?

Pope: That instinct arose when I was first becoming a practicing environmentalist. I read a famous essay about the role of religion in the environmental crisis, by Lynn White, in which he said Christianity was substantially responsible for the attitudes that led to the environmental crisis. I read it when I was 25, and that was very formative in causing me to see churches, not so much religion, [but] churches as not useful institutions, and I paid no attention to them [from there on].

Then in 1997, the Patriarch was having this conference in Santa Barbara. I was invited, I thought it looked interesting and I decided to go.

Two weeks before the conference, Walter Capps, who was the Congressman from Santa Barbara, and was going to be the keynote speaker, died of a heart attack. I got a call asking if I would fill in for him. I didn’t have a speech ready, or even thoughts formed.

So, I went back and looked at the Lynn White article and [realized] I’d totally misunderstood it. It didn’t say what I thought it said, and I was pretty sure most of my fellow 1970s environmentalists, the Earth Day generation, had also misunderstood it.

So I got up and said, “We screwed up.” And in the essay, White makes a distinction that in Western Christianity, sin was something you did, [it was] a behavioral thing. But in Eastern Christianity, sin was more about your beliefs and attitudes.

It was a matter of wrong understanding. So I said, since I’m guilty of wrong understanding and since I’m speaking to a fundamentally an Orthodox crew, because that was mainly who was there [the conference was in a Greek Orthodox Church in Santa Barbara].

They had these guys there who were Greek Orthodox bishops in black robes with big, big silver crosses, and one of them came up to me and said, “Well, now that you clarified sin, you know what comes after sin, don’t you?” And I said, “Yes, contrition…I want you to tell me that I need to take a pilgrimage to Mount Athos.” He said, “Yeah, but you’ll have to go up on your knees,” and I said, “Well I might be a little too old for that.”

But I did conclude that the failure to interact with religion, not so much as a belief system, but as an institutional system, has been a very significant failure in the environmental community, the Earth Day environmentalist generation. If I was to speak more broadly now, I would say I think also the failure to engage with the workplace.

There was an isolation from the rest of society. Somehow the environmentalist [movement] was going to exist in its own hermetic institutional vacuum [in] the counterculture. We were going to create a whole new culture. That turned out to be not nearly as easy as we thought, and that was a mistake.

Epstein: White’s essay is fascinating; some of my atheist and agnostic students at Harvard are still debating it to this day. It starts out seeming to say all of religion was harmful to the environment. Then at the end, he actually suggests adopting the perspective of St. Francis of Assisi, which is hardly a secularist conclusion.

Pope: That was a part I didn’t understand when I was 25.

Epstein: Anyway, as a humanist/secularist/atheist I tend to agree that environmentalists — and leaders in other progressive causes — should do more to engage religious institutions. But I’m at TechCrunch now because we need to engage with the great secular religion of America, which is business, and especially the tech business.

And you just said that there’s also a failure to engage the workplace. How has the environmental movement failed to engage businesses and workplaces? How does that relate to the work you’re doing with Michael Bloomberg?

Pope: The environmental movement was sort of strictly for people who buried automobiles. In spite of the fact that the first Earth Day had been substantially financed by the United Auto Workers and came out of conferences the Auto Workers conducted.

The idea that work needed to be environmentally positive instead of simply something you were trying to clean up after, didn’t ever take off because we didn’t talk to anybody who actually [understood] what most people did for work. We could have had a much stronger relationship with the labor movement, at least the progressive parts of the labor movement.

In fact, we could have had a much stronger relationship with communities of color, and particularly at that point, African Americans. But we didn’t do any of those things because we were the counterculture.

I did a lot of work to try and rebuild those relationships with organized labor, with the Blue/Green Alliance; that was an important part of mine, and more substantial actually, than what ended up happening with the churches.

Epstein: In A Climate of Hope you talk about Elon Musk and Tesla. Which companies in the Silicon Valley tech community have you found to be especially worth engaging with?

Pope: My engagement with Silicon Valley really came at the end of my time with the Sierra Club. I did a fair amount of work with people in Silicon Valley, from let’s say 2012 to 2016, trying to solve the problem that elected Donald Trump president, which is the problem of the decline of American manufacturing.

I don’t think I was particularly effective. But I was very surprised by an encounter with K.R. Sridhar at Bloom Energy.

K.R. makes fuel cells, he’s a NASA engineer who built reverse fuel cells in space for NASA, and decided to reverse the technology to something useful back here. He founded a company, and I heard about it, and I was interested and intrigued, and I went to see and meet. He took me around what at that point was a bench-scale factory, but they were making product.

We were sitting down, and he said to me something about how he would like to be able to make this technology in the United States, but he didn’t think he’d be able to. Being at that point quite naïve about manufacturing, [I assumed it was] because of wages. He sort of laughed at me, and said, “The reason advanced manufacturing has weakened in the United States has nothing to do with American wages; wages are a trivial part of the cost structure.

[K.R.’s concerns] were with the lack of political priority US politicians were placing on manufacturing — for example, when someone he knew wanted to locate a silicon chip factory on Long Island they were told that in a drought the golf courses would get priority for access to water.

I began to go to a bunch of conferences and worked with a bunch of people including now Congressman Ro Khanna, who wasn’t then a congressman. Ro was working in manufacturing at the Obama Administration, and we tried to get the Obama Administration to really do something serious about manufacturing in a much more high-priority way, and we were never able to get that level of attention from them.

K.R. eventually was able to manufacture in the US, because the Delaware government did prioritize manufacturing — for which it was vigorously attacked by the Tea Party, which of course is now the base for pro-manufacturing President Donald Trump.

And if you look at Tesla, for example, it did take over the old NUMMI plant in Fremont, and did it over very successfully. But we were never able to get Tesla to agree to work with the United Auto Workers. So again, people went off and did their siloing thing.

In the America in which I grew up, there was a lot of social solidarity coming out of the oppression of World War II. That solidarity was spent down and not replenished, and that’s a big source of the dilemma we’re in now. We don’t act like we’re all on the same boat together.

Image via Getty Images / alashi

Epstein: There was a moment in 1990 where you told the New York Times, “We’ve suddenly entered a time of great fiscal conservatism. All the causes that had been nearest and dearest to people’s hearts, they now don’t want to vote taxes or bonds for.”

Was that, in retrospect, a moment of generational change? Is that when even your generation, the early Baby Boomers, began to take a pragmatic or “efficient” approach to social change, rather than fulfill the promise of the idealism it had expressed before?

Pope: In retrospect, that was the moment it became clear that Ronald Reagan’s “Greed is Good” had fundamentally corroded that social solidarity that I just referred to. That, “We are all in it together, America,” was becoming, “I’m on My Own America.”

I don’t think I fully understood that in 1990, in fact, that was when the fruits of the Reagan Revolution really began to be felt. At that point, we had Republican Presidents [for over two decades]; Jimmy Carter was the outlier.

When Bill Clinton then came in, in 1993, three years later, he came into a world that was constrained by Reagan’s legacy [of] Greed was Good.” And remember, the Boomers started out distrustful: “Don’t trust anybody over 30.”

So it became, “Don’t trust anybody in government.” That was the piece of Reagan’s poison that got ingested: “Don’t trust government, trust the market. Be a consumer, not a citizen.”

Epstein: That makes me want to ask: how closely you align with the idea of a Green New Deal?

Pope: Millennials [are] the generational cohort that has gathered around the Green New Deal. Obviously, lots of people, such as Bernie Sanders [and GND co-drafter Senator Ed Markey] are not of that generation at all, so it’s not unique to the Millennials. [But] a startling statistic I saw the other day is that American parents now spend a substantially larger number of hours directly with their children.

Epstein: I have a young kid, and yeah, it’s time-consuming.

Pope: There was a figure Ross Douthat had in a column the other day: [nearly] twice as many hours a week are spent [on parenting] than average American parents spent [in the 1960s].

[Kids now] are much more in structured organized activities than my generation was. My parents didn’t see me from 8:30 until 6:30. From 3:30 to 6:30, I was with other kids with no adult supervision at all. It was very different.

I think the Green New Deal is a reflection on the fact that this is a generation that got a lot of parental care, and then when they got out into the workplace there were no opportunities. So it’s like they’re having their version of the Great Depression experience. I know we’re not in the Great Depression, but the sense of economic, the fact that the economic system doesn’t work if you work hard is intensely felt by Millennials.

They’re looking at the generation ahead of them and saying, “You guys don’t know technology as well as I do. Why do you have all the good jobs? Well, because you’re older, you got there first.”

And now there are no new good jobs. People, have to do the gig economy. The idea of having to do the gig economy when I grew up, that wasn’t there.

Maybe not if you were African American, but otherwise, you got an education, you got a job. End of conversation, nothing to worry about.

So it’s not accidental that people are reaching back to the New Deal. It may actually may not be quite the right metaphor logically, but emotionally, it’s that sense of economic solidarity that’s being tapped into. So it’s great, it’s what the time needs.

Epstein: Are you saying, “It’s great, but…“? Is there a significant difference between what you are calling for and what you see in the Green New Deal?

Pope: There’s a bunch of stuff that’s been wrapped in this Green New Deal that has to do with broad economic policy, some of which, which I don’t really think belongs in the same basket. But I’m not going to comment about it, because [on those issues] Mike Bloomberg and I might not agree, and neither of us might agree with the Green New Deal.

I don’t think that the problem with employment in the United States is the lack of a national job guarantee. I think the lack of a national employment policy is the problem.

But I don’t think that [would be best addressed by] a federal job guarantee. I don’t think that would be the solution I would adopt. But I don’t think that’s the heart of the Green New Deal.

Some in the Green New Deal [camp] seem to think we need to do this very, very rapidly and disruptively. I actually believe we can do this quite rapidly and non-disruptively.

I actually think my version of the Green New Deal ends up not being nearly as expensive as other people’s versions. That’s what Mike and I spend our time looking at: if we use market forces well, and if we repair market failures, what will happen?

We think we get what we need if we repair market failures. So, we’re more optimistic than the advocates of the Green New Deal.

But the thing that they want to do, I think we want to do. We agree about the outcome, we just think it’s easier to get there [by market forces].

Epstein: Have you had any personal opportunity to discuss that with any of the leaders of the Green New Deal, either Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or her colleagues?

Pope: I have not, because I’m on the West Coast. I haven’t talked to any of the leaders.

Epstein: It seems like it would be an interesting conversation.

Pope: It would be an interesting conversation.

Coming soon in Part 2: Details about the $500 million pledge, including a promise to make this one of the most inclusive and diverse philanthropic gifts ever; an admission of a key time when Bloomberg and Pope were wrong; and, how do you balance ego with inclusion when you’re working with one of the most successful businessmen of all time?