Money from big tech companies and top VC firms is flowing into the nascent “virtual beings” space. Mixing the opportunities presented by conversational AI, generative adversarial networks, photorealistic graphics, and creative development of fictional characters, “virtual beings” envisions a near-future where characters (with personalities) that look and/or sound exactly like humans are part of our day-to-day interactions.

Last week in San Francisco, entrepreneurs, researchers, and investors convened for the first Virtual Beings Summit, where organizer and Fable Studio CEO Edward Saatchi announced a grant program. Corporates like Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft are pouring resources into conversational AI technology, chip-maker Nvidia and game engines Unreal and Unity are advancing real-time ray tracing for photorealistic graphics, and in my survey of media VCs one of the most common interests was “virtual influencers”.

The term “virtual beings” gets used as a catch-all categorization of activities that overlap here. There are really three separate fields getting conflated though:

- Virtual Companions

- Humanoid Character Creation

- Virtual Influencers

These can overlap — there are humanoid virtual influencers for example — but they represent separate challenges, separate business opportunities, and separate societal concerns. Here’s a look at these fields, including examples from the Virtual Beings Summit, and how they collectively comprise this concept of virtual beings:

Virtual companions

Virtual companions are conversational AI that build a unique 1-to-1 relationship with us, whether to provide friendship or utility. A virtual companion has personality, gauges the personality of the user, retains memory of prior conversations, and uses all that to converse with humans like a fellow human would. They seem to exist as their own being even if we rationally understand they are not.

Virtual companions can exist across 4 formats:

- Physical presence (Robotics)

- Interactive visual media (social media, gaming, AR/VR)

- Text-based messaging

- Interactive voice

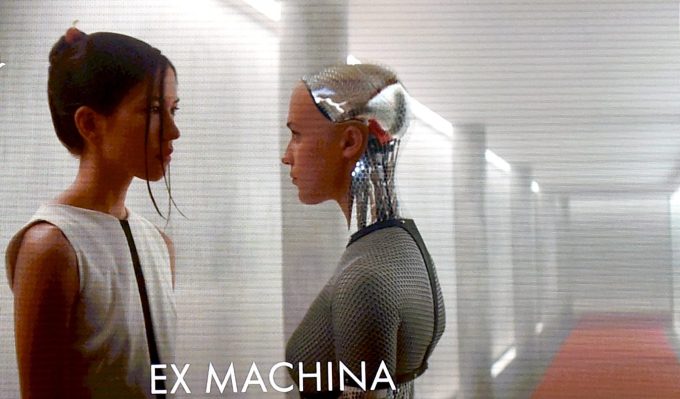

While pop culture depictions of this include Her and Ex Machina, nascent real-world examples are virtual friend bots like Hugging Face and Replika as well as voice assistants like Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri. The products currently on the market aren’t yet sophisticated conversationalists or adept at engaging with us as emotional creatures but they may not be far off from that.

We’re in the early stages of evolving virtual assistants from computers spitting out basic information in a robotic voice based on a human input — like a voice-based Google search — to virtual companions whose voices and conversational abilities feel more human. Passing a Turing Test isn’t the point here though: we don’t need our virtual companions to be exactly like humans, just to be able to engage with us in a high-EQ manner and convey emotional sensitivity (the way Pixar can make a robot or toy cowboy that we feel an emotional connection to).

At the Virtual Beings Summit, Ryan Germick (a principal designer at Google) explained this best. The dozens of staff now working on the editorial side of Google Assistant are giving it the persona of a “hipster librarian,” he said.

Rather than approaching Google Assistant as being a library, a map, and a search tool (as they used to), they’re building it to be a librarian, a navigator, and a researcher. A being that’s helping you. To use his Wizard of Oz reference, they are “giving the tin man a heart”.

The core technology for virtual companions is within natural language processing — natural language understanding of user inputs and natural language generation to create the output. Computer vision for recognizing a human’s facial movements and the surrounding environment is also needed for virtual companions to visually interact with humans in a way that feels natural (if they have a visual component at all).

At the Summit, Google’s Lukasz Kaiser highlighted OpenAI’s GPT-2, which generated a coherent story about a unicorn based on a two-sentence prompt. It’s a major challenge to train an AI to have hard-to-quantify characteristics like creativity and personality — as Kaiser said, “If the reward to optimize for is fun, what is ‘fun’ exactly?”

Meanwhile, Los Angeles-based Artie featured its Wonderfriend engine for developing avatars that engage us on our phones and use the phone camera for emotional recognition. Alonso Martinez of Mira also shared his efforts to bring virtual companions to the physical world with little robots — cute ones you’d expect to see in the Pixar movies he used to work on — that track facial expressions to make eye contact and respond with sadness or excitement.

Virtual companions are the real “virtual beings”. A being exists as its own entity; it interacts independently with the world around it. It is not merely a character whose words and behavior are scripted in the background by humans.

Virtual companions represent a potential operating system of the future: a conversational medium for navigating our personal and professional lives. The companies behind Alexa, Google Assistant, and Siri want those virtual companions to operate across device types and have personalized interactions with each of us throughout the day.

As so many activities like flight booking, clothes shopping, stock trading, appointment scheduling, and route mapping shifted from web browser to mobile, they see those activities shifting to their virtual companions (enabling them to capture some of the economics of those transactions).

Since the same AI can create different personas for each end-user and more data creates an advantage in training AI, the incumbent tech giants have a strong advantage in this field. Startups are unlikely to get ahead of them in creating a generalist virtual companion but startups creating valuable AI technology are natural acquisition targets for them and there is room to create niche virtual companions specialized in achieving a certain personality or supporting technical tasks in specific context.

Humanoid character creation

Advances in voice synthesis and photorealistic graphics are getting close to allowing characters in videos, games, and AR/VR experiences (including avatars of ourselves) to look and sound like real humans. Examples are the Troll demo of real-time ray-tracing by Unreal as well as the multilingual David Beckham video by Synthesia and synthetic Barack Obama and Donald Trump voices by Lyrebird.

In addition to making media experiences like games, VR, and animated films lifelike, these breakthroughs are useful across numerous industries, allowing actors to be inserted into scenes they were never in, commercials to be translated into any language with the actors’ mouths moving accordingly, digital avatars of ourselves to try on clothes before we order them online, and more.

Creating humanoid characters that humans control the words and actions of isn’t creating an independent virtual being, in my opinion, but a world in which we have realistic avatars of ourselves representing us online is a radical new paradigm for social interaction and self-expression than expands our definition of each human’s being. And of course, this technology can be applied to a virtual companion to represent the companion visually as a human…that’s the scenario many people envision when they hear “virtual beings”.

In part through new techniques like ray-tracing, the graphics technology for this is nearly at a state of tricking people into thinking what they are seeing is real. A barrier to broader adoption is the processing power it takes, in particular to render those graphics in real-time for any interactive format.

According to John Macinnes of Macinnes Scott (which created more human-looking characters for Call of Duty and a Sotheby’s exhibit where guests’ facial movements are replicated by avatars of Barack Obama and Donald Trump), we can only render hyper-real avatars of humans in real-time on high-end VR headsets and PCs currently.

More advanced graphics cards, led by NVIDIA’s GeForce RTX, are pushing the frontier here, but rollout of 5G telecommunications infrastructure may be the most important shift to come. Macinnes said 5G will enable this processing to occur on the cloud instead of on-device, unlocking its compatibility with smartphones and any other internet-connected product.

At the Summit, USC professor Hao Li presented the use case of 3D avatars of ourselves to try on clothes while online shopping and said his Pinscreen app already has partnerships with big retailers in Japan to test it out.

In addition to appearance, natural-looking movement and response to environmental changes is critical for developing life-like characters or virtual companions presented as human or animal avatars. DeepMotion CEO Kevin He’s physics simulation models the bone and muscle structure of a human or animal body so avatars move in a corresponding manner, be it proactively from their actions or reactively from being pushed. The startup Humen.ai is also working on movement: they’re using computer vision to create videos where an avatar mimics the pose from a human in a source video so you can record yourself moving in a manner you want the avatar to in the digital realm.

The big startup opportunities here are to either create a core piece of technology for creators around the world to use in building and maintaining their applications or to leverage such technology to build a “killer app” in one vertical like avatar-based shopping.

These technologies don’t just make more advanced graphics and audio possible, they are making it accessible for content creators without large corporate budgets, greatly expanding the market. As humans create avatars of themselves online, it will also open markets for digital clothing (see The Fabricant) and other digital products to customize those avatars like we already see in games like Fortnite.

Virtual influencers

View this post on Instagram

The third field within the Virtual Being space is the growing experimentation with fictional characters who build and engage with a fanbase online like real human celebrities would. These “virtual influencers” interact with the real world using social media.

Examples are characters like Brud’s Lil Miquela and Spark CGI’s Cade Harper which strive to look like real humans, as well as animated characters like Shadows’ Astro and the vast landscape of parody social media accounts like Jesus, SocalityBarbie, and the sadly retired Startup L. Jackson. Virtual influencers aren’t new but they are an exciting opportunity for storytelling and building an omnichannel IP franchise.

The Virtual Beings Summit featured presentations by Ash Koosha (whose Auxuman startup created Yona) and Cameron James Wilson of Diigital (a “digital modeling agency” that creates and manages virtual influencers like Shudu, Margot and Zhi). The new ability to create near-photorealistic humanoid characters established a new niche within the celebrity market and the press attention for Lil Miquela and Shudu in particular has driven interest from entrepreneurs and VCs.

Unlike virtual companions and humanoid character creation technology, the virtual influencers market is purely a content game though. The words and behavior of virtual influencers are scripted by the humans who control them, and that’s likely to always be the case since the whole benefit to running a virtual influencer business is the greater control you have over the influencer’s personality and storyline relative to a real human influencer’s.

While some entrepreneurs are using newer graphics tools, the business models for virtual influencers — humanoid or not — are the same as any human celebrity: advertising & brand deals; selling merch, books, & exclusive content; and leveraging the stardom to secure roles as characters in films, shows, games, etc.

The big startup opportunity here is to create a studio whose IP portfolio of virtual influencer characters and stories constitutes a next-generation Marvel or Pixar. The competitive risk is that any existing owner of IP from film, TV, gaming, books, or elsewhere can choose to create and operate social media accounts for their fictional characters. But social media-first, cross-platform storytelling is likely as differentiated enough format of storytelling to provide an opening for new companies to carve out their own turf in the entertainment market.

How dangerous is the rise of virtual beings?

For all the opportunities I’ve touched on, virtual beings should cause concern as well. These technology advances can be used, intentionally and unintentionally, for harm.

The least concerning of these three categories is virtual influencers. Assuming people are aware that they aren’t real humans, virtual influencers aren’t more dangerous than any fictional character or human influencer in pop culture is. They can be bad role models and bullies, and they can create unrealistic perceptions of human beauty, but these are issues we already face with celebrities and the widespread use of Photoshop.

Humanoid character creation poses a serious threat, however, since it can be used deceptively. Avatars of real humans could be used to create fake videos that embarrass or incriminate them, as could synthetic audio files.

Innocent people are already getting killed by vigilantes due to the spread of false information on social media without these technologies, so their availability makes it too easy to destroy someone’s life. At a societal level, fake media of public figures could create political crises, manipulate the stock market, and create a broader distrust of all media content due to their inability to sort fact from fiction.

Moreover, efforts by many game developers to make characters in violent video games ever more lifelike could lead to players experiencing real mental trauma or desensitize them to the harm of real-world violence.

These risks warrant more attention by the technologists advancing these technologies and by the public in general. I’ve found that these concerns are an afterthought to most of the entrepreneurs in the virtual beings space.

They acknowledge them but aren’t themselves committing much effort to address them. It’s natural that the development of any new technology progresses faster than the societal consideration of the technology’s downsides.

Fortunately, these threats are also business opportunities: technology is needed to counter them and a wide range of business, government, and consumer customers would pay for such technology. That means talent and capital will flow toward the development of defensive tools as well. Software to detect synthetic video and audio content, and to track authentic content (perhaps using a blockchain), constitute a whole new subset of cybersecurity.

The rise of virtual companions presents a great unknown here. We are still a few years from virtual companions that feel like their own beings to most people but it’s not too far off.

Is it healthy for humans to build relationships with AI beings? How much do we want to incorporate such virtual companions as members of human society? How many human jobs will these companions displace?

These are profound questions within the history of humanity — we haven’t invented a new type of independent being before — and likely to be the subject of fierce political conflict in the future.

Expect to see and increase in VC and corporate investment in virtual companions and humanoid content creation technologies, and cybersecurity to counter their negative uses. I believe the virtual influencer category will also see a surge of VC funding them see the hype subside.

All in all, this broader virtual beings space will blur the lines between fictional characters and real-world beings though. This creates big business opportunities for creatives and technologists alike, albeit not without downsides that we need to address.