When Alex Karp needed funding for a young start up named Palantir in 2005, dozens of investors said “No.”

He was trying to sell them on the idea of a high-powered analysis platform that could scan multiple databases simultaneously— a tool that government officials and corporations could use to tackle complex problems.

“It was very scary since doing enterprise software [from] 2005 to 2009 was a little bit like starting a circus in the middle of Palo Alto with engineers,” Karp says, “Enterprise is a dirty word and that’s the business we’re in, and government is also not very popular in the Valley, [we combined] both.” [See our interview with Karp above]

Today, funding is not an issue.

Palantir, a team of 250-plus engineers nestled in downtown Palo Alto, has raised $90 million in Series D financing at a $735 million valuation— the company exclusively told TechCrunch. The round was led by co-founder Peter Thiel’s The Founders Fund and included Youniversity Ventures, Glynn Capital, Miriam Rivera’s Ulu Ventures, Jeremy Stoppleman, Ben Ling, and a couple of high-profile NY funds.

Although Palantir did not disclose whether it’s profitable, the company says revenues have at least doubled every year for the last three years. And yet this nearly billion dollar company— yes, that’s billion with a big fat “B”— remains a wallflower in Silicon Valley.

Foursquare, a company founded in 2009, has at least 208 posts on TechCrunch. Palantir, founded in 2004, has one. Unlike the most buzzed about startups in tech, Palantir is not in the social game. It doesn’t dispense daily deals, nor does it accept mobile payments and it certainly does not Tweet.

It is an obtuse, difficult-to-explain product that is mainly used in Washington— the government makes up 70% of its business and the rest is dominated by private financial institutions. That may sound painfully boring but Palantir’s user-friendly analysis program is becoming a major player in the war against terrorism and cyber espionage, stimulus spending accountability (Palantir is literally powering the administration’s efforts to identify fraud in stimulus projects), health care, and even natural disasters like the recent earthquake in Haiti.

This year, the platform famously helped researchers at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto expose a cyber espionage ring called the Shadow Network, which was stealing classified materials from India’s Defense Ministry.

Where there’s a crisis, it’s safe to say that Palantir is probably not far behind.

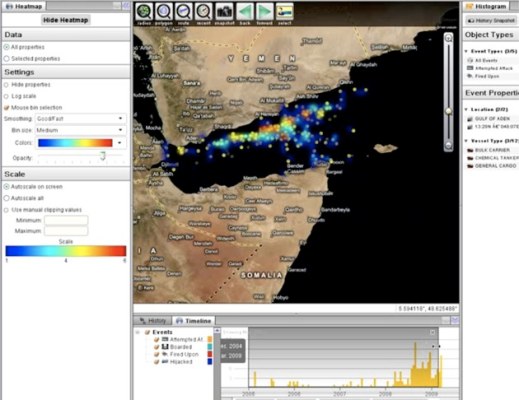

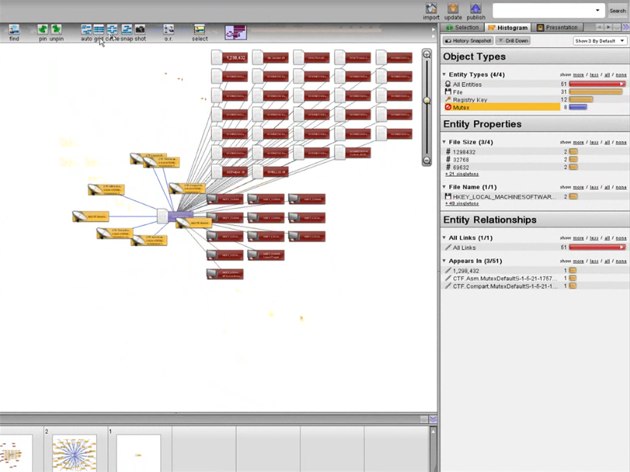

Screenshot of a Palantir project:

What is Palantir?

To understand Palantir, it helps to start at the origin.

The company is named after the Palantir stones of Lord Of The Rings, which allowed the characters to connect with other stones and see nearby images. The fundamental point of Palantir is to take reams of data and help non-technical users see critical connections and ultimately, the answers to complex problems. The product is a child of PayPal, born from the start up’s methodology for combating fraud:

“They had this massive problem of essentially cyber fraud…they tried algorithmatic approaches…one of the things about that is it doesn’t work really well because the opponent is highly adaptive…What you need is a human mind that’s adaptive,” Karp says.

That would form the foundation for the Palantir platform, which merges human-based algorithms and a powerful engine that can scan several databases at once on an incredibly fine, granular level. It comes in two flavors: Government and Finance. The basic system, which is designed to look like software from a Hollywood spy thriller, accepts huge databases and allows users to slice the information in seemingly innumerable ways. Unlike PayPal’s model, Palantir is also designed to be highly sensitive to a variety of security needs.

At Palantir’s headquarters, Shreyas Vijaykumar (Forward Deployed Engineer) and Shyam Sankar (Director of Business Development) walked us through one simulation.

We looked at a hypothetical E.Coli outbreak in Detroit, Michigan. We knew the approximate date of the outbreak and the fact that victims purchased meat at two different grocery chain. Using Palantir we were able to identify all the store locations in the area, find the meat distributors, isolate the stores that shared the same distributors and ultimately narrow it down to two distributors where the contamination may have originated. Not exactly fighting terrorists, but a pretty neat 10-minute activity. If it sounds convoluted, you can check out some of their demonstration videos here.

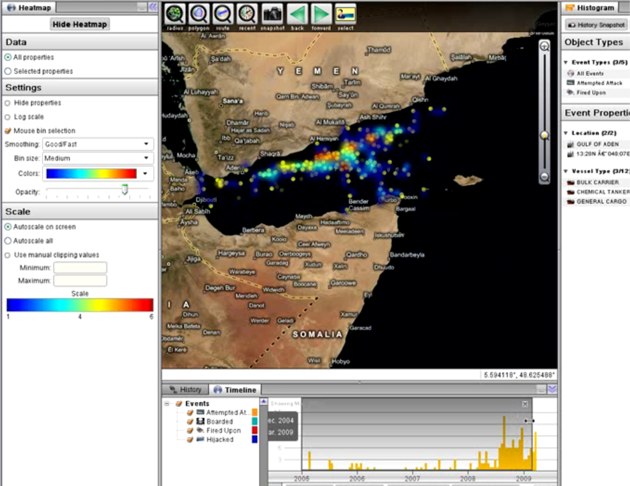

Heat map of Somali pirate attacks:

Unlike the many contractors it competes against, Karp emphasizes that the company does not provide a service, it will always be product oriented.

That dogged loyalty to refining the flagship product permeates Palantir’s offices. For example, a software update is released every month— on the Palantir Government side, the engineers name the update by assigning an element from the periodic table and designing a shirt to commemorate the new update (yes, 250-plus t-shirts are printed each month). That spirit is further reinforced by the engineer-centric model— virtually every single employee is an engineer and roughly 27-years-old. Predictably, the office space is punctuated with extra-large bean bag chairs, a small community of dogs, board games, Halo (even conference rooms are named after parts of Halo), a working train set, paintings of Carebears, and even a bubble machine that spews bubbles when someone breaks the build.

Of course, there is a downside to an engineer utopia working feverishly to perfect a platform. If everyone’s an engineer, who sells the product?

The answer is no one.

There is no publicist, no sales or marketing team and Karp adamantly believes that there will never be one. He says he is perfectly content to let word of mouth drive his business, in press and in sales. He knows he could multiply his revenues by building out a sales team, but he think it would ultimately detract from the mission:

“If you are iterating on a product that you want to be important three years from now, it’s better to have engineers figuring out what the core issues are and then iterate against them. If you want to optimize on revenue [for the] next quarter…you want to be heavy on a sales force. We’re long on dealing with the most important problems…and short on what happens in the near term.”

It’s hard to imagine a billion-dollar company without a sales team, but then again Palantir is getting pretty darn close.