The early 2000s were the era of user-generated content. Companies like Associated Content and Shareasale rewarded content producers richly – one friend of mine made millions on YouTube in 2004 because he was one of the few serial content producers on the platform. The future was going to be broadcast in all of its gritty glory. Bloggers would win forever and ever. The voices of the Internet masses would be heard through the Twitter and Facebook megaphone.

Inherent in this plan was the idea that UGC was somehow purer and more desirable than commercial communications. This era lasted from about 1993 until about 2008. This was the era of an unfettered Internet, of the Cluetrain Manifesto, and of open source everything. The ethos was pure anarchy in its best light. No one would control your output, no one would stand between you and your fans, no one would take a cut of your money. Bloggers, tweeters, and Facebookers would get rich simply because they existed.

“Twitter was built at the tail end of that era,” writes designer Mike Monteiro. “Their goal was giving everyone a voice. They were so obsessed with giving everyone a voice that they never stopped to wonder what would happen when everyone got one. And they never asked themselves what everyone meant. That’s Twitter’s original sin. Like Oppenheimer, Twitter was so obsessed with splitting the atom they never stopped to think what we’d do with it.”

Interestingly, I think we now know what they’d do with it. And what Facebook would do with it. And what the Internet would do with all of that UGC. They would sell our content to programmatic advertisers and put us directly in the crosshairs of every social media analyst with a fringe political agenda. And now the users who were generating that content are about to fight back.

First, Facebook and Twitter (and Instagram, to a degree) should take defections by high-profile users seriously.

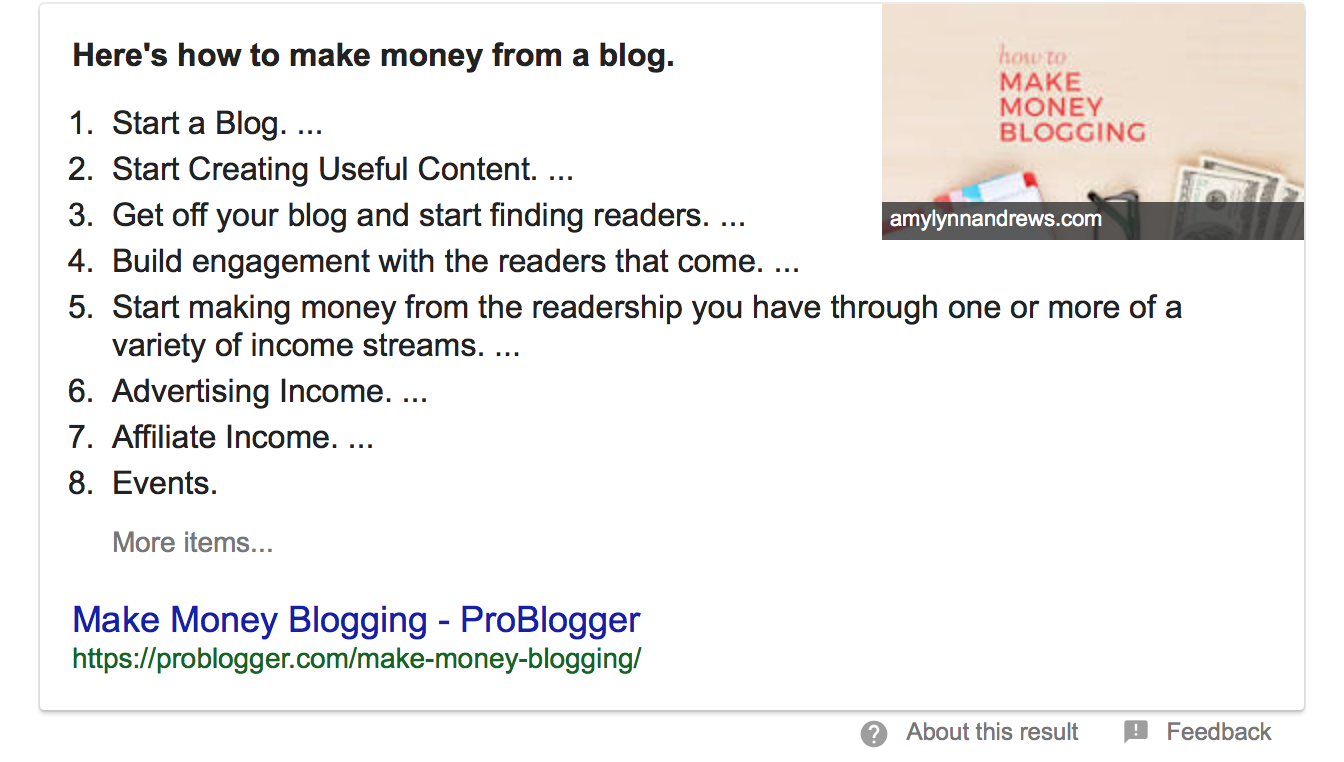

Early users of all social media joined because of that original promise of fame, fun, riches, and relationships. They leave now because the walled gardens are overrun by marketing and trolls. This can be said of every major platform. No one is safe. What works online? A repurposing of the original DIY ethos into, essentially, this guy:

So we stand on a precipice waiting to drop. What media social media gives rise to in the next decade is anyone’s guess – rich people are betting on VR but that’s still a tough sell. We are in an interstitial period, like the point in the late 1980s when you could still compare the nascent Internet to CB radio. We don’t have maps to future territories. Will we collectively give up, splayed naked on the screen for all to market to? Will we turn inward using apps like Signal and Telegram to ensure no one can see us? Will we turn social media into more of a money-making channel for folks with six-packs and mischievous grins? Or can we expect something else entirely?

What I know is that it is, in short, a turn toward the end of oversharing. In a fun interview with Stephanie Alys I did a few weeks ago we came to the conclusion that everyone would be naked on the Internet for 15 minutes. Privacy has eroded to the point of no return, at least on the current Internet, and I suspect that tools that give us back some of that privacy will be the in-demand apps of the next decade. User generated content was supposed to replace newspapers. It did. User generated content was supposed to inject itself into politics. It did. User generated content was supposed to tear down the paywalls built by publishers. It did. We got what we wanted. Now what?

We need new and better tools. We need to bring back some of the truth-telling tricks used by newspapers to ensure content isn’t just content. We need to rebuild democracies world-wide to be impervious to digital meddling. It is my undying hope that our failure to manage the spoils of the UGC revolution hasn’t completely destroyed the institutions that ensured the best rose to the top on merit, not on clicks.