After drones became available to private citizens around the world, bad actors found ways to use them for nefarious purposes, like spying on corporations, carrying contraband across borders and into prison yards and, sadly, turning the aerial robots into weapons. Drone crashes also put people and property in harm’s way.

Provo, Utah-based Fortem Technologies Inc. has raised $5.5 million in a new round of seed funding to keep the skies, and people below, safe as we enter the drone era. Signia Venture Partners and Data Collective (DCVC) led the deal.

The so-called counter-drone market is bustling with activity. Other startups in this category include: Airspace, Guard From Above and threat detection firms like Department 13 or Dedrone to name just a few.

Signia partner Ed Cluss and DCVC managing partner Matt Ocko said Fortem’s approach is differentiated from others thanks to its proprietary radar technology.

According to Fortem CEO Timothy Bean, the company has developed a compact radar that enables drones to detect fast-moving aircraft up to 3,000 meters away. The idea is to ensure that as drones enter our airspace, they stay well-clear from one another and manned aircraft, even traveling at 100 miles per hour.

Fortem acquired its core radar technology in 2016 from IMSAR, and over the last year has adapted it so that the system can be exported around the world, leased or purchased outright within the typical security budget for a variety of venues, and can work with any security-grade drones.

DCVC’s Matt Ocko said, “Fortem’s radar uses less power than a light bulb, and has similar capabilities to one of those building-sized radars that you saw crouching ominously in the Arctic in the late 90s.” He views Fortem as a startup that will make “BLOS,” safe and acceptable to regulators. In the trade, BLOS means drones flying autonomously beyond a human operator’s line of sight.

The company can integrate its radar into drones of the type that are typically used for physical security, professional aerial photography or delivery by drone. It also can install its radar on the ground around a particular venue or city that wants to monitor the skies.

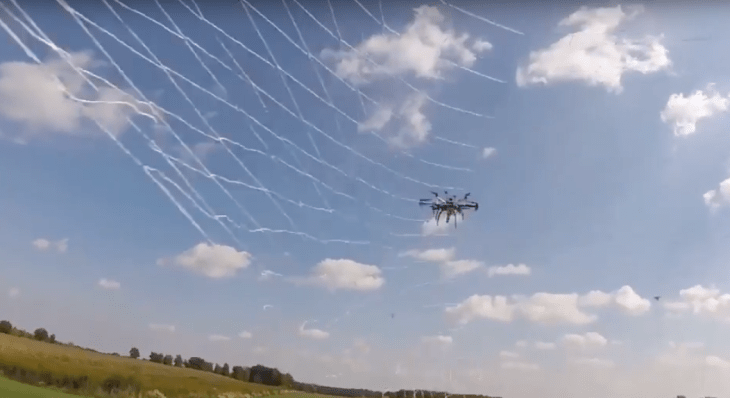

However, Fortem also makes its own DroneHunter UAV, which can track the movement of aircraft approaching, classify what kind of vehicles they are and, in the case of smaller drones, will literally net and tow them away or drop them with a parachute so they don’t land on anyone’s head.

The company is developing collaborative capabilities for its DroneHunters, so users will be able to run fleets of them to counter multiple intruders simultaneously. While it is working with government agencies, and is generating revenue, Bean said he could not disclose further details about the company’s clients.

Signia’s Ed Cluss said outside of military demand for this technology, Fortem’s commercial applications are very wide-ranging. He expects Fortem’s DroneHunter, software and radar will be used by businesses and municipalities to monitor infrastructure such as stadiums, data centers, water and power plants, schools or resorts. Cluss asked, “How does one live in a drone world and feel safe? With a modern air safety and security company. That’s how we see Fortem.”