In recent weeks, several high-profile incidents have been blamed on infrastructural elements of an increasingly frequent scapegoat: the internet.

U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May made a call to renege on human rights and “regulate” cyberspace. Australia has insisted to surveillance alliance Five Eyes that encryption must be compromised in the name of safety.

Politicians — and public opinion — are beginning to slowly turn against parts of the internet, from encryption to bots, without considering the fact that the tools themselves are not bad. It is how people use them that can be problematic.

Policymakers’ animus against the internet isn’t new: it’s part of a long trend of suspicion about this medium that challenges all media. Their feelings toward regulation of the web are often muddied by broader trends of political ambivalence toward the actual mechanics of the web.

Recently, Australian Prime Minister Malcom Turnbull said, “the laws of mathematics are very commendable, but the only law that applies in Australia is the law of Australia.”

Statements like this are striking examples of how politicians like Turnbull stubbornly refuse to learn about the infrastructure of the internet before claiming to know how to solve the problems that result from its complexities.

Such accusations, similar to recent blanket indictments by politicians against the political use of bots, fail to recognize one important fact: regulation should not be levied against tools themselves, but against particular uses. For instance, calls to ban bots of social media miss the fact that these automated software mechanisms allow for myriad positive, and even benign, activities such as queuing posts.

Politicians like Turnbull stubbornly refuse to learn about the infrastructure of the internet before claiming to know how to solve the problems that result from its complexities.

While social bots and encryption can allow for the ability to, say, anonymize communication, it is people that use anonymity for means either democratic or repressive, legal or criminal. Our team’s research at the University of Oxford has found that while a variety of political actors have used social bots in efforts to manipulate public opinion, some governments have overreacted to the technology rather than the usage.

What we need is more complex conversations, and sensible policy, about how to minimize negative aspects of digital anonymity while still maintaining the internet’s essence as a free-information medium that can benefit society.

State-based efforts to manipulate political online communication are very worrying. Freedom House’s last global survey of internet censorship found that freedom on the internet declined for the sixth year in a row. Governments, and powerful corporate entities, are consistently limiting democratic aspects of the web.

It would be a grave mistake for politicians to continue this trend of minimizing freedom online. The entropy unleashed by new levels of access to information is an event that has historical precedent that we should observe and learn from while we still have the chance.

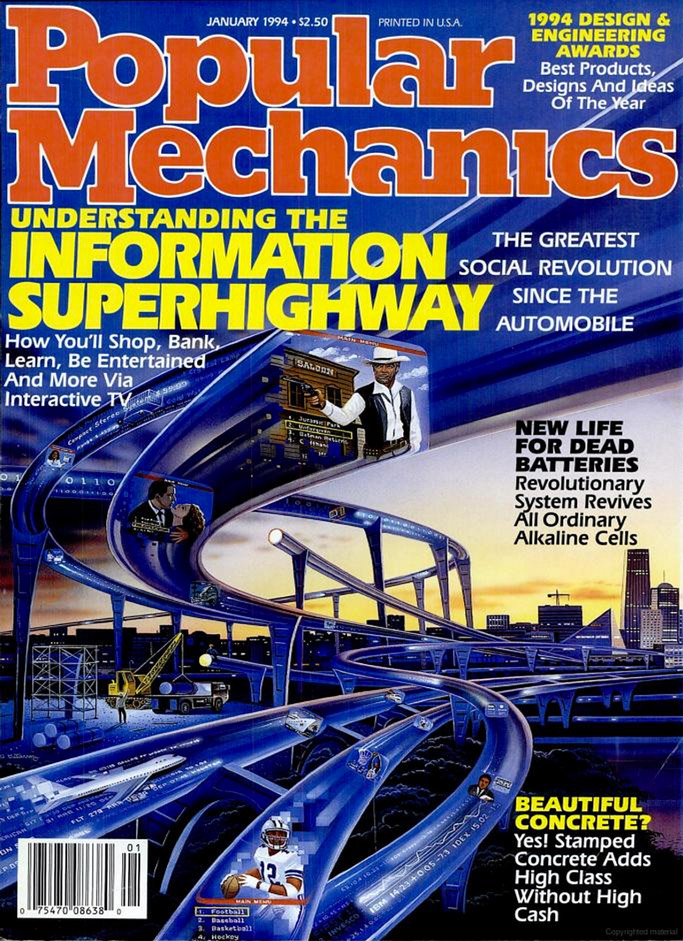

Nate Silver, for instance, has pointed out that the original information revolution began with the invention of the printing press in 1440.

“The amount of information was increasing much more rapidly than our understanding of what to do with it,” writes Silver, “Paradoxically, the result of having so much more shared knowledge was increasing isolation along national and religious lines.” Our current predicament is markedly similar.

In 2015, The Economist compared the invention of the smartphone to that of the printed book. A recent study by the International Data Corporation found that the total amount of data generated every year, the “digital universe,” will approximately double every year from 2005 to 2020.

The digital dam has cracked — the deluge of information holds promise and peril — but we are in a unique position to choose order over chaos. It is only natural that we are having trouble navigating this overflow of information, but it would be wrong to regard this predicament, or the tools associated with it, as the exclusive problem.

In a 2012 report the National Intelligence Council said that individual empowerment could prove a solution to society’s greatest plights. To turn against the tools that make the internet a free information medium would undermine the positive side of individual empowerment.

This side enables innovations like Taiwan’s anti-fake news bot or bots that combat the isolation of echo chambers online, it enables individuals to keep their bank details and health information secret and it encourages entrepreneurs to drive positive societal innovations.

The need for carefully considered data and internet policy is, however, indisputable. Tim Berners-Lee has suggested that giving consumers the right to own their data and regulating online advertising would be good starts. To wantonly call for regulation that infringes on human rights, however, will in the end result in a less safe — and information rich — society.

We must ask ourselves, what aspects of the internet are intrinsic to democracy and are they divisible from those necessary for control? Freedom of speech and the right to privacy are essential to democracy and need to be preserved online. When it comes to harm, and specifically to one’s right to free speech infringing upon another citizen’s well-being or rights, we must establish boundaries.

There is a profusion of data about known disinformation or terrorist recruiting campaigns online — social media companies must be more open with this information. Sharing it with researchers could allow for solutions to be developed while preventing overregulation or outright public sharing of proprietary knowledge. Another long-term solution is to keep democratic values in mind while designing new technologies. As John Markoff writes,“how we design our increasingly autonomous machines will determine the nature of our society and our economy.”

We’re currently living in a time digital strategists have deemed the data wild west. The next decade the data policies set could determine the basis of digital rights for the foreseeable future. Reason is most useful at times when it seems least reasonable — we would do well to approach digital problems with nuanced solutions and informed policy that ensure liberal democracy within the digital sphere.