Since the advent of the modern ticket era, speed has been the name of the game. Whether it was the first person to get in line, or the first ping to hit the server, the winners in the world of ticketing have always been a step ahead.

Over the last 15 years on the internet, that competition has risen to super-human levels, with bots becoming virtually unbeatable. For average fans, that reality makes the process of buying tickets time-consuming, confusing and often expensive. It has also caused periodic and collective uproars that get covered by the media as examples of the ticket industry’s greediness, inefficiency or both.

The current scandal involving radio personality Craig Carton is the latest uproar about the markets brokeness. Regardless of who is to blame — other than Carton — scandals like this one, and two others over the last six months, the ticketing underbelly seems as large as ever. Amidst that girth, even real progress can be interpreted as more of the same.

For fans who have had enough of trying to keep up with the ticket market, there is movement toward a slower and hopefully better future. On the backs of massive growth in demand for live music over the last 10 years, performers are figuring out new and innovative models to satisfy demand by creating more supply. While residencies are the long-standing model for Las Vegas, this unending demand for live music is spreading the model across the entire country.

Last month’s inaugural Slow Food festival took place in Denver and included 305 speakers, 70 exhibitors and thousands of attendees, all ostensibly gathered to focus on the festival’s core mission that “food should be available for everyone, not just the privileged classes; and food should be fair and just for all.”

If you replace the word “food” with “ticketing,” it serves as a good, and unofficial, manifesto for the nascent “slow ticketing” movement.

Over the last six months, both the need and potential solutions have been on full display. In addition to Phish’s 13-show Baker’s Dozen run last month and Bruce Springsteen’s Broadway onsale last week, residencies are everywhere. Along with Phish, Billy Joel’s residency at Madison Square Garden is another successful model. Garth Brooks has also been a major innovator in creating more supply by continuing to announce shows in one city until primary demand no longer supports primary ticket sales.

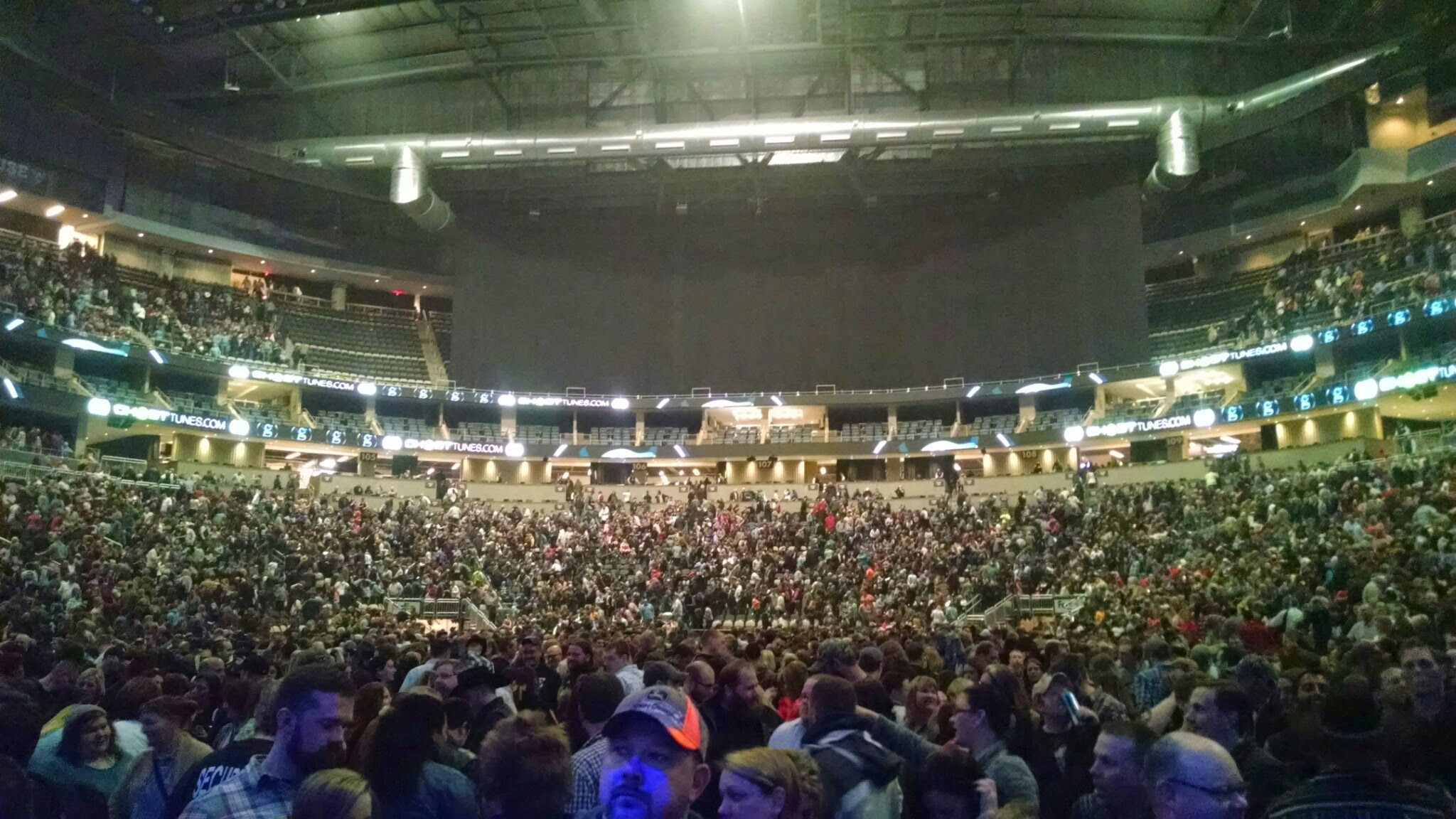

Photo courtesy of Flickr/fatherspoon

Now in its eighth leg, the Garth Brooks World Tour started in 2014 and has played in almost every major city across the country. The longest of those runs was Minneapolis, in which he sold 201,000 tickets across 11 shows. In total, the ongoing tour has sold more than $300 million and broken ticket sales records in 11 states.

Across these residency models, while the secondary market plays a role, it’s not the same roll that fans have grown accustomed to, where secondary is a proxy for the entire market and where prices are often listed for multiples of original face value. As an example, for Billy Joel’s October show at Madison Square Garden, the cheapest ticket available on TicketIQ is $95, $10 below the cheapest face price.

Bands like Phish and the Dead have long used constant touring as the centerpiece of their business model. For such a model, mail order has been the most reliable way to get tickets in the hands of real fans, and it’s a distribution strategy well-suited for 30-50 date tours with defined start and end dates (Joel excluded).

Unfortunately, as a model for the scalable digital age, the kind manual of verification mail order calls for just doesn’t work. A single mail order can take minutes to process, while a web order using authentication like Ticketmaster’s Verified Fan takes milliseconds. Carton’s and other’s ability to perpetrate large-scale fraud is the result of a product that lives simultaneously in the realm of paper and digital. As most of know firsthand, it is often a frustrating, confusing, uncertain and expensive consumer experience.

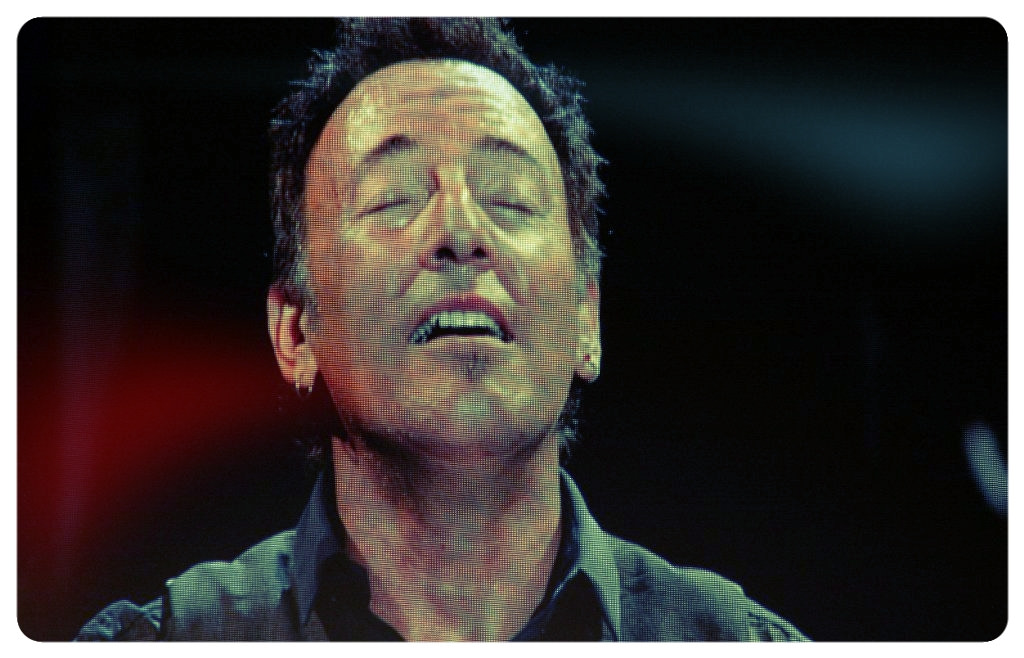

Despite the fact that last week’s Bruce Springsteen on Broadway onsale sold less than 80,000 seats, it may be the most compelling piece of evidence of slow ticketing progress, at scale. The onsale was tasked with the daunting challenge of matching 79,000 seats of supply with millions of Springsteen fans, and countless brokers.

With 970 seats available for each show, it’s the definition of intimate for an artist who established himself in the stadium-rock era of the 1980s. As a point of comparison, Springsteen’s last tour played at 47 arena venues in North America and grossed more than $300 million.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/El Coleccionista de Instantes Fotografía & Video

The onsale for Springsteen on Broadway was managed using Ticketmaster’s Verified Fan product, which launched earlier this year and has now been used for more than 50 tours and generated more than 2 million registrations. Perhaps not surprisingly, the first tour to use it this year was Dead and Company, an offshoot of the Grateful Dead. While Ticketmaster has not released information on the number of people who registered for the Springsteen Verified Fan onsale, there’s no question there’s enough demand to sell out for years.

Immediately after the initial onsale, another 10 weeks was added to the run. As a comparison, star-driven Broadway shows like Hamilton and Dear Evan Hansen continue to sell out months in advance, even without their original stars. During the peak of Hamilton-mania, when Lin Manual Miranda in the role of Hamilton, between 100 and 600 tickets were showing up every night on the secondary market.

For the 1,300 person Richard Rodgers theater, that’s anywhere from 10 percent to 45 percent of the seats available. In the two weeks after Lin Manuel left, but the rest of the original cast remained, there were more than 800 tickets available for a handful of shows. For shows this month, with all of the original cast long gone, the average quantity of tickets available on the secondary market is still 398, which is about 25 percent of seats in the venue.

Of the 79 shows that have gone onsale for Springsteen on Broadway, anywhere between 2 percent and 5 percent of tickets at the Walter Kerr have shown up on the secondary market. In talking to many fans, I’ve only heard about successful verification from people who not only bought Bruce Springsteen tickets on multiple occasions in the past, but also used them.

The fact that more fans are using their tickets means that even with tickets starting at $1,500 on the the secondary ticket market — 20 times face price — the size of the overall secondary market is a fraction of what it could have been without something like Verified Fan, or a full-scale mail order operation.

Over the last 20 years, The Boss has been at the center of more ticket controversy than perhaps any other artist. The most public of those was settled in 2011, when Ticketmaster paid $16.5 million to Springsteen fans who, looking to buy tickets for the 2009 “Working On a Dream Tour” were sent directly the secondary market at prices several times face value. 2011 was arguably the peak of the “fast ticket” era, when brokers and bots claimed dominance over real, human fans.

The slow food movement was first coined in 1986 and has since come to apply to a broader worldview that encompasses all walks of life, including everything from cities to money. Wikipedia now lists 19 different slow movement applications. If current trends toward more effectively matching supply to demand continue to develop, ticketing could be the twentieth application, and that would be good news for everyone in the ticket business, fans and artists included.