It has occurred to me that perhaps TechCrunch pays insufficient attention to slurry, sediment, silt, sludge, mud, and muck; to canals, earthworks, levees, dikes, dredges, and the Army Corps of Engineers; to the vast engineering works, with lifespans measured in decades, that literally reshape our world. So last weekend I boarded a bus hired by the Dredge Research Collaborative.

This wonderfully obsessive and obscure group of infrastructure aficionados, guided by Wired writer and Rhode Island School of Design professor Tim Maly, has held an annual “DredgeFest” event every year since 2013. This year it was a tour of that vast artificial hyperreality just upstream of San Francisco and the Valley — the California Delta.

“We own the only high-rate offloader west of the Mississippi,” Jim Levine says at our first stop, the massive megaproject called the Montezuma Wetlands, with some justified smugness in his voice. “Slurry it up to 15% … pump the sediment 4 miles at 20,000 gallons a minute … last year we took in about a million [cubic] yards … probably half of all the dredging in the bay.”

“Wow,” an awed student breathes in reply, “that’s a lot of dredge.”

The entire Delta is, basically, a lot of dredge. Once it was a huge wetland carved by a network of intertwined, constantly shifting waterways. Then came the 19th-century gold rush. Miners upstream in the Sierra washed away entire rock faces with high-pressure water, creating a gargantuan “pulse” of sediment that filtered downstream, its traces still visible in the San Francisco Bay today. Meanwhile, settlers began to cultivate the Delta. Chinese laborers built the first delta megaproject; a colossal array of levees to (aspirationally) hold back floods.

The descendants of those levees wall the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers today — and the peaty land of the islands behind them has subsided to a depth which in places hits 26ft/8m below sea level. On Sherman Island, where the Sacramento and San Joaquin meet, we stood in those depths, looking what felt like way up to the riverbanks, jokingly advised to look for cracks in the levees.

Of course what really worries Californians is earthquakes. Sherman Island, and its levees, keep the brackish Bay water out of what’s sent south by the California State Water Project. If it were to be inundated by a levee breach, salinity would increase so much that “we’d have to shut down the pumps” carrying water south, said an engineer from Ducks Unlimited (no, really) as he showed us around the site.

If this doesn’t seem like a tenable long-term solution to you, you’re not alone. Governor Brown and co. are currently promoting a $15 billion plan to carry water under the Delta to Southern California, courtesy of two giant tunnels. This is, to put it mildly, controversial. Others have proposed converting farmland back to natural wetlands. Which is of course even more controversial.

There is no such thing as a megaproject without fierce opposition. Even the Montezuma Wetlands project — which, elegantly, tops up subsided lowlands with dredged sediment, to regenerate the kind of wetlands which originally existed — attracted enormous hostility and resistance. The project was birthed in 1991: it did not launch until 2003, after 12 years of legal battles.

Now, in the shadow of a massive wind farm (its existence perhaps prompted by the project’s $150,000/month PG&E bill) a slow restoration of two thousands acres of wetlands is underway, and should continue for at least another decade. In an era when “tech” usually means something obsoleted within a few years, there is a certain grandeur to projects with this kind of scale and lifespan.

Even outside of cities, most of the population of California lives in a fundamentally artificial environment, courtesy of what can be considered an ongoing engineering project that dates back more than a century: the transformation of the Delta and the Central Valley into some of the world’s most productive farmland, while keeping the South alive with water from the North, the Owens Valley, and the Colorado River.

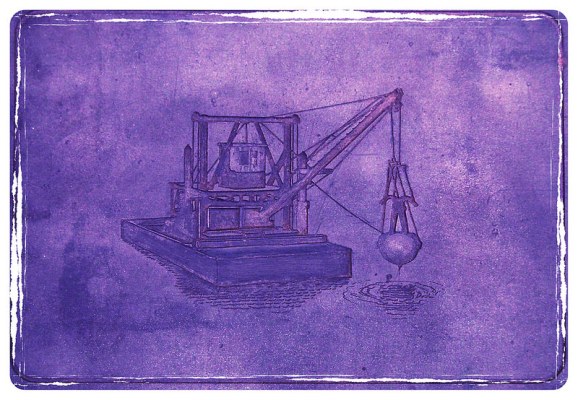

Some of this history has been captured at the Dutra Museum of Dredging (no, really) in Rio Vista in the Delta. (Sorry, hacker tourists; they’re open by appointment only, and prefer groups of 10 or more.) There I learned that the clamshell dredge was one of the cutting-edge world-changing technologies of its day. It’s still in wide use, but of course it’s not “tech” any more. As technology ages, it becomes infrastructure, and grows deeply boring to most.

The friend who invited me out to DredgeFest is a professional infrastructurist himself — except that his is in orbit. One day the descendants of his satellites will be both as unsexy, and as crucial, as the dredges you might glimpse from BART or the bayside from time to time, without really noticing. And why should you? Like most infrastructure, they are much too important to be allowed to be interesting.