Sometimes, more medical information is a bad thing. The influential United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends against most women getting genetic screenings for their susceptibility to breast cancer. Why? Because the tests are imperfect: for every woman who gets tested for genes associated with onset breast cancer, even more will falsely test positive, leading spooked patients into needless surgery or psychological trauma. Super cheap genetic testing from enterprising health startups, such as 23andMe, have complicated cancer detection for us all by increasing the accessibility of imperfect medical information.

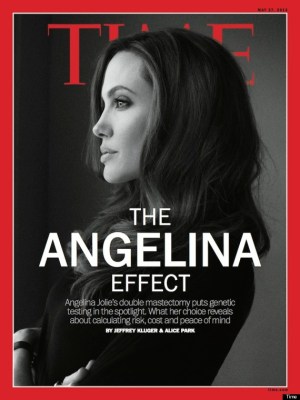

After discovering a mutated BRCA1 gene, known to increase the likelihood of breast cancer 60 to 80 percent, actress Angelina Jolie underwent a radical preventive double mastectomy. Her brave confession in the New York Times brought much needed attention to breast cancer awareness, but it’s dangerous in the hands of a statistically illiterate population.

For instance, as New York Times statistical guru, Nate Silver, once reminded me, while breast cancer mammograms are 75 percent accurate, a woman who tests positive only has about a 10 percent chance of actually getting cancer. Since the vast majority of women don’t have cancer, there are far more women who will falsely test positive (here is a helpful blog post with the numbers worked out). Most importantly, surveys reveal that many people don’t understand the math behind false positives in cancer testing, and may make uninformed decisions as a result.

The same math holds true for the mutated BRCA1/2 gene of Jolie’s confession: researchers estimate that a tiny 0.11 to 0.12 of women have the faulty gene. “I believe in doing genetic testing for BRCA1/2 with appropriate counseling,” writes University of Southern California’s David Agus, one of Steve Jobs’ cancer doctors. The answers are not simple in this case and require experienced professionals to discuss with the patient.”

Traditionally hundreds of thousands of dollars to test, a cottage industry of cheap genetic testing has sprung up. 23andMe, one of the most popular, offers the service for as little at $99, and has even dared to weigh in on the BRCA controversy on the company blog.

Citing a new study that found no negative emotional consequences from patients after learning about their BRCA1 mutation, 23andMe concludes, “The findings are important given that a frequent criticism of direct-to-consumer testing is based on the assumption that it causes either serious emotional distress or triggers deleterious actions on the part of consumers.”

Given the absence of evidence for serious emotional distress or inappropriate actions in this subset of mutation-positive customers who agreed to be interviewed for this study, “broader screening of Ashkenazi Jewish women for these three BRCA mutations should be considered.”

Sometimes, however, voluntary surveys don’t tell the whole story. In its cover story on Jolie’s decision, TIME magazine recounts the tale of one woman who likely had unnecessary preventative surgery after learning about a genetic defect. “She freaked out and had a bilateral mastectomy,” said Otis Brawley, chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, who worried that this patient’s particular mutation was not as troubling as she worried it was.

Interestingly, TIME’s author, Kate Pickart, argues the financial costs of genetic testing has stalled a mass run on genetic tests. Even a new provision under the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) only mandates 100 percent insurance coverage for patients with a family history of genetic flaws.

But, at just $99 (and probably far less in the future), financial barriers are crumbling. This isn’t to say that genetic screening is bad, it just complicates things for the rest of us, especially those who don’t understand statistics. The more women get tested, the more false positives exist, the less confident patients and physicians become in a course of action.

Maybe our only hope out of this cheaper testing spiral is technology that makes detection more accurate and more predictive. One promising solution is a new bra that constantly monitors deep tissue for cancerous signs (below).

So, perhaps, before long, we will innovate our way out of this dilemma.